Translate this page into:

Challenges of Using Methadone in the Indian Pain and Palliative Care Practice

Address for correspondence: Dr. Vidya Viswanath, Department of Palliative Care, Homi Bhabha Cancer Hospital and Research Centre, A Unit of Tata Memorial Centre, Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh, India. E-mail: drvidya21@gmail.com

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

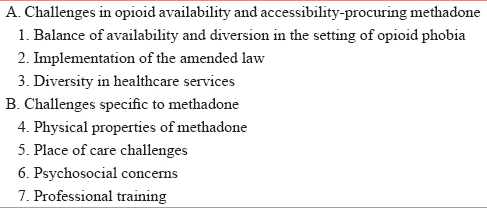

Palliative care providers across India lobbied to gain access to methadone for pain relief and this has finally been achieved. Palliative care activists will count on the numerous strengths for introducing methadone in India, including the various national and state government initiatives that have been introduced recognizing the importance of palliative care as a specialty in addition to improving opioid accessibility and training. Adding to the support are the Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), the medical fraternity and the international interactive and innovative programs such as the Project Extension for Community Health Outcome. As compelling as the need for methadone is, many challenges await. This article outlines the challenges of procuring methadone and also discusses the challenges specific to methadone. Balancing the availability and diversion in a setting of opioid phobia, implementing the amended laws to improve availability and accessibility in a country with diverse health-care practices are the major challenges in implementing methadone for relief of pain. The unique pharmacology of the drug requires meticulous patient selection, vigilant monitoring, and excellent communication and collaboration with a multidisciplinary team and caregivers. The psychological acceptance of the patient, the professional training of the team and the place where care is provided are also challenges which need to be overcome. These challenges could well be the catalyst for a more diligent and vigilant approach to opioid prescribing practices. Start low, go slow could well be the way forward with caregiver education to prescribe methadone safely in the Indian palliative care setting.

Keywords

Methadone

methadone challenges

methadone in India

opioid

opioid prescribing practices

INTRODUCTION

Palliative care physicians across India lobbied to gain access to methadone for pain relief. Now that this has been achieved, our real work begins. The 1985 narcotic drug and psychotropic substances (NDPS) Act made obtaining opiates for pain almost impossible with the multiple layers of licenses.[12] At this point, there are relatively few opioids available and legal in India and these are morphine, methadone, tramadol, fentanyl, and meperidine, (hydrocodone and oxycodone are legal but not available).

While the introduction of methadone in India presents societal and medical challenges, there is clearly some strength to the Indian context for the safe introduction of methadone.

In the government sector:

-

The 2014 Amendment to the NDPS Act improves the scope of opioid availability[3]

-

The national program in palliative care provides a model program implementation plan, a framework of operative and financial guidelines by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and a training module on palliative care[4]

-

The introduction of Palliative Medicine as a broad specialty by the Medical Council of India (MCI)[5]

-

The recognition of palliative care as an integral part of the noncommunicable diseases program along with a separate budget allocation[6]

-

The National Health Policy 2017, which mandates attainment of the highest possible level of health and well-being for all and thrusts on comprehensive primary health-care package, geriatric health care, palliative care, and rehabilitative care services[7]

-

Recognition of two World Health Organizations Collaborating Centers in the country for palliative care – The Trivandrum Institute of Palliative Sciences (TIPS) for Training and Policy on Access to Pain Relief and the Institute of Palliative Medicine (IPM), Calicut for palliative care and long-term care.[8]

Another strength of palliative care in India is the strong driving force of community networks and NGOs. The National Network of Palliative Care is one of the largest community-driven palliative care programs in the world.[9] Pallium India has affiliates in over ten states.[10] The IAPC-Indian Association of Palliative Care certificate courses;[11] the IACA-Indo American Cancer Association fellowships;[12] the National Fellowship from the IPM[13] with eHospice scholarships;[14] the collaborative effort of the INCTR-International Network for Cancer Training and Research;[15] the EPEC-India (Education in Palliative and End of Life Care),[16] and the TIPS initiatives provide education and training to physicians, nurses, and allied health-care providers across India. TIPS is the “hub” of a Palliative Care Extension for Community Health Outcome (https://echo.unm.edu/) training program with video conference teaching sites throughout India.[17] The Jiv Daya Foundation supports some palliative care centers across India with free morphine supply.[18]

In the medical fraternity, the national cancer grid (NCG) connecting cancer centers from across India, has included opioid rules, the amendment, and palliative care resources in its website.[19] A multiprofessional medical organization for compassionate care called the “Mathura Declaration” has also taken root among the neurology and critical care physicians.[2021] The International Children's Palliative Care Network is slowly gaining acceptance in India.[22]

The Indian Journal for Palliative Care reaches interested physicians, with the print journal and online and other didactic sessions. India has needed an alternative to morphine and an inexpensive long-acting opioid medication. In this article, we will outline the challenges ahead for the safe and effective use of methadone [Table 1].

THE BALANCE OF ACCESS AND AVAILABILITY VERSUS MISUSE AND DIVERSION FOR ALL OPIOIDS

The lasting legacy of the International Narcotics Control Board[23] and the NDPS Act of 1985[24] is the strong prejudice against opioids in the society even for medical use. The International Narcotics Control Board, established in 1968, and the NDPS Act focused on illicit use and created a convoluted hierarchy and complex licensing requirements to strangle the use of opioids in medical practice. There was absolutely no balance[25] in the use of opioids in India. They were simply unavailable. For two decades, the palliative care community, the Government and Civil Society Alliance worked to change the mindset of the policymakers and bring about the NDPS Amendment in 2014.[126] The objective of the law is now expanded from controlling illicit use to promoting appropriate medical use. The new regulation, moving forwards, eliminates the need for multiple licenses; applies to all potential medical use of approved opioids (pain and dyspnea relief), and addresses lack of training in opioid usage.

The Drug Controller Office/Food and Drug Administration in the Department of Health is solely responsible for implementation. This office will regulate the medical institutions that stock and dispense opioids with accountability, including a responsible registered medical practitioner trained in the medical use of essential narcotic drugs (ENDs). The law also created the Central Rules for the ENDs which is applied uniformly across the country. Methadone, legal for opioid dependence since 2007, was approved for pain management in 2016.[3]

The challenge is to manage patients in pain, especially cancer pain, in a sea of nationwide opioid phobia, recognizing that when opioids are available liberally, there might be some unintended consequences, including accidental overdose and diversion.[27] Now that the laws and options are beginning to support “freedom from pain,”[28] the challenge is in walking the tightrope between celebration and caution.

IMPLEMENTATION OF THE AMENDED LAW THAT GOVERNS OPIOIDS ACROSS INDIA

Although opioids are accepted as essential for cancer pain globally,[2930] accessibility, and availability remains limited in India[23132] as in various parts of the developing world.[3334] In 2017, the NDPS Amendment of 2014 has not yet been incorporated in all Indian states even though the law simplified the needed laws for each state. Multiple licenses, procedural delays, poor stocking, and under treatment continue. The state governments are unfamiliar with the purpose of the amendment, and the drug manufacturers are concerned about dealing with opioids as the systems to differentiate licit and illicit use are not yet in place.[1] The medical fraternity suffers from lack of awareness and an apathetic attitude toward the role of opioids in pain relief.

The solution to this challenge is the ongoing commitment and activism from the civil society[1] in addition to the global support for policies and funding.[3536] Hence, palliative care practitioners in every state along with key civil society members from different sectors including law, media, and health policy need to be champions for a continued nonconfrontational engagement with the authorities to make the anticipated reforms of the law a reality.[1226] Education of the medical fraternity at every opportunity through workshops and online courses focusing on opioid availability, accessibility, and training for safe use should be widespread and ongoing.[1263137] We need to address the poor public awareness of palliative and end of life care,[38] so that they come to expect high quality of care.

DIVERSITY IN HEALTH-CARE SERVICE DELIVERY

Diversity in India is its identity but becomes its nemesis when it comes to health care. There is complete lack of uniformity in health-care availability, practices, protocols, standards of care, and access to medications and continuity of care.[38394041]

The reality of cancer centers is that patients are sent back to their home just when their need for opioid peaks and opioid availability is at its worst. Palliative care referrals often occur on the day of the patient's discharge just before returning home. Finding a source for uninterrupted supply of morphine in itself is a logistical challenge.[4042] Medical practice is driven by the ability to pay. Futile intensive care for the wealthy, or the practice of LAMA (Left Against Medical Advice) for the poor are the unfortunate choices due to the lack of the legal framework or policies for patient autonomy and good end-of-life care practices.[3943] The huge socioeconomic divide contributes to health-care practices that are not uniform.[41]

Physician training is quite variable. For a registered medical institution to procure, stock, and dispense morphine, a trained doctor is needed, but there is ambiguity in the definition of the training. A well-defined curriculum and educational program is needed to ensure uniform training.[44] While Kerala is a global training hub, most of the other states have a paucity of educational programs and palliative care services.[9] Current undergraduate medical teaching does not include the WHO Step Ladder[45] and use of opioids in providing pain relief. The result is that the drug is denied, maligned, or improperly prescribed. Due to the lack of training of health-care providers[38] in palliative care, prescriptions for opioids are often irrational. Patients are sent with a one-time prescription of a transdermal patch with no prior titration or assurance of follow-up. It is ironic that a fentanyl patch can be more available than morphine.[31]

Where palliative care exists, mostly the focus is cancer patients. Palliative care services for non-cancer chronic diseases is limited despite the symptom burden of chronic kidney disease, HIV, neurological diseases, and the burgeoning geriatric population.[4046]

Ideally, district hospitals should train doctors, nurses, pharmacists, and social workers in primary palliative care to ensure the continuity of care and opioid access. Although the National Program in Palliative Care was created in 2012, it lacked budget allocation and streamlining of care.[26] The National Health Policy of 2017 has included major features relevant to palliative care. It recognizes the need for continuity of care along with community and home-based care with appropriate legal and regulatory system for opioid access or the need for an educational curriculum.[7]

An attitudinal shift in the medical community toward the pain management and role of opioids is needed through extensive and inspiring educational activities.[1] Even more important is sensitizing the young medical and nursing graduates to the basics of palliative care.[47] Ongoing communication with the regulatory bodies like the Medical Council of India(MCI) is in progress.[1]

PHYSICAL PROPERTIES OF METHADONE

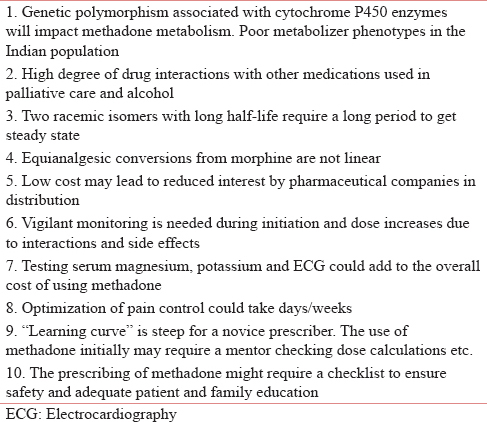

Methadone is unique and its properties, though compelling, will be challenging in India.[484950] The unique pharmacology of methadone will be addressed thoroughly in this supplement (reference Sunil et Kashelle). Challenges of methadone pharmacology [Table 2].[48495051525354555657]

Due to its pharmacodynamics and the pharmacokinetics methadone is therapeutically effective, has no ceiling effect, has a simple route and needs less frequent administration. It is cheaper and has a broad spectrum of action, making it a sound second-line analgesic.[50]

The challenge lies in the ease of use to initiate and monitor methadone, the side effects, and the drug interactions. While initiating methadone in an opioid naive patient, during the titration phase, balance should be maintained between inadequate analgesia due to insufficient dosing and systemic toxicity due to overdosing. Patients should be aware that optimization of pain could take a few days.[51525354]

While switching to methadone, the two major methods are the “Stop and Go” and the “progressive” method using equianalgesic conversion tables and further dose reduction accounting the incomplete cross-tolerance. The complexity here is the interpatient variability, unclear evidence about dose conversion and requisite clinical experience. Consideration of comorbidities for dose calculations and monitoring adverse effects for dose titration is also needed.[495354]

The challenge is to ensure that the prescriber is trained to prescribe, the choice of patients is carefully made, methadone is initiated and monitored in those who merit it and the follow-up is planned with care and changes are made by the prescriber only. Pharmacists in India are not trained to cross-check prescriptions and alert the physician if there are errors in dosing. The physician will need to understand the drug and conversions, focus on the interactions and dose modification, and train the family and caregivers. Initially, methadone needs to be managed by specialists trained in pain and palliative care.[50] Practically, in the Indian setting, methadone could be used in the inpatient and outpatient setting. A trained physician can initiate, monitor, follow-up, and document it with the assistance of well-instructed family caregiver. It is also essential that the potential risks and benefits are discussed with families/patients, and concurrent drugs that prolong the QT interval are avoided. The principle of “start low, go slow” needs to be followed. Networking with colleagues, creating interest groups, and documenting case studies will be invaluable.

In some Western countries, it is mandatory for the prescriber to train and obtain certification to prescribe methadone. While this would cause increased barriers to prescribing, it might also ensure greater safety. For example, in Canada, a physician can only prescribe methadone after obtaining an “exemption” under Federal Narcotic Act 56.[58]

THE CHALLENGE IN THE DIVERSITY IN THE SITES OF CARE

For many patients, their medical records are carried in a folder and remains with them. They may see specialists, primary health center physicians, Ayurvedic doctors, and their pharmacists. Patients also use Integrative Medicine providers (Ayurveda, Homeopathy, and Siddha), go city hopping, and doctor shopping. They might hide this behavior from the treating physician.

Each of these well-meaning health-care providers could recommend medications that might interact with methadone. Or, they might adjust (or stop!) the methadone without understanding the pharmacology. As the physician prescribing the methadone, there is no way to be sure of the full complement of pharmacologic interventions in all patients. Polypharmacy[59] very often remains invisible and is a high risk to the patient.

Complications of disease-directed therapy could be blamed on the use of methadone. Any incident involving an overdose or accidental death could be quite difficult for the field of palliative care in India. In other countries, methadone is prescribed through “triplicate prescription”[60] which is monitored by the state/provincial regulatory body.

Morphine remains the gold standard for cancer pain[61] in India and patients comfortably down-titrate their morphine dose when chemotherapy provides pain relief. This may not be as easy with methadone, especially when associated with chemotherapy-induced emesis or toxicity. Communication and collaboration are required among different caregivers.

It would be prudent to prepare a checklist with details of alcohol or substance abuse, drug interactions, history of structural heart disease, familial sudden death, unexplained syncope and the serum potassium and magnesium values, QT interval if available, history of nonadherence, or self-adjusting medications.

A reliable caregiver will need, to learn about the risks and the need to closely communicate about medication changes. Benefits of using methadone can outweigh the risks in the palliative care population with methodical assessment and multidimensional approach.[62] There have been studies reported with methadone titration done on an outpatient basis[636465] and at home[66] under careful monitoring with good, multidisciplinary longitudinal care. Building that in India is another challenge!

THE PSYCHOSOCIAL CHALLENGE

Guidelines in developed countries, advocate a baseline ECG, and electrolyte monitoring. This would mean adding to the investigation burden causing physical, financial, and psychosocial distress. Although methadone is priced the cheapest, these tests could add hidden costs. It could even reinforce the fear that pain medications are detrimental and better avoided. For patients and caregivers who read the internet and other media sources, the fact that methadone is used for addiction[67] could be a cause for concern but writing specific notation on the prescription “for pain management” may help. Thus, counseling patients and family caregivers before starting methadone should become the norm. Clear and consistent longitudinal communication with the family is imperative.

THE TRAINING CHALLENGE

The concern is that any untoward incident with methadone could be detrimental to the cause of palliative care. Palliative care providers have a responsibility in these early phases to use methadone carefully in selected patients. There is a huge gap between demand and supply and uninterrupted supply of oral morphine in all parts of the country. Creating a Safety Circle[68] is paramount. This needs a relationship built on trust between a responsible doctor and a patient. Along with promoting awareness, ensuring opioid availability and educating the society, safe use of opioids under supervision is critical.

Learning from the experiences with opioids in the West, it is important that along with regulation, training, and certification of health-care providers, “creating clear blue waters”[69] between opioid manufacturers and formulation of practice guidelines is also necessary.

A methadone pain management training program for doctors, nurses, and pharmacists along with uniformly implemented opioid laws would be a step in the right direction. Sessions on methadone could be integrated with opioid availability workshops and training in palliative care. Well-framed guidelines accessible online as in the NCG website could be a useful resource. Research in palliative care could include situation analysis of the availability of palliative care, the knowledge of the NDPS Act, problems in accessing treatment, ethical dilemmas faced by health-care providers among others.[70]

Networking and collaboration between professionals and major centers in key geographical locations with whom practitioners in the area can consult and follow-up are invaluable. Working with a physician colleague or another center and documenting every case into a registry or a specially formed body could be a future resource and the cornerstone for good clinical practices.

A future publication by 5–10 physicians’ experience of 10 or 20 consecutive patients for pain management in their practice will have a major value to Indian physicians wishing to use methadone for pain management.

CONCLUSION

Challenges do not mean that methadone cannot find a place in India. It could well be the catalyst to create a working group of committed people from the civil society to implement the amended law and improve the accessibility of opioids in India. The cornerstones of education, policy, and opioid availability should be addressed together to demystify and transform opioid practices, especially methadone for pain management in India. It remains certain that any medical prescription is bound by the cardinal principles of medical ethics[71] and methadone is no different. The challenge is to find the balance between when, where, and for whom to prescribe, how to follow-up and document, collaborate, and communicate, so that a clear path to move forward is created. Prescribers must be compulsive and practice due diligence in their opioid prescribing practice including methadone.

Start low, go slow is not just about dosing but implementing the program safely too!

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

I am very grateful for the guidance and support from all the contributing authors and Dr. Naveen Salins throughout the writing of this article.

REFERENCES

- Civil society-driven drug policy reform for health and human welfare-India. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53:518-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Improving access to opioid analgesics for palliative care in India. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24:152-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Directorate General of Health Services. Available from: http://www.dghs.gov.in/content/1351_3_NationalProgramforPalliativeCare.aspx

- [Google Scholar]

- Specialist palliative medicine training in India. Indian J Palliat Care. 2015;21:257.

- [Google Scholar]

- Congratulations, Everyone. Palliative Care Finds a Place in India's National Health Policy 2017 Pallium India-Care Beyond Cure. 2017. Available from: http://www.palliumindia.org/2017/03/congratulations-everyone-palliative-care-finds-a-place-in-indias-national-health-policy-2017/

- [Google Scholar]

- And World Health Organization, 2014 Global atlas of palliative care at the end of life. London: Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance Google Search; Available from: http://wwwgooglecoin/searchq=Alliance%2C+W.P.C+and+World+Health+ Organization%2C+2014+Global+atlas+of+palliative+care+at+the+end+of+life+London%3A+Worldwide+Palliative+Care+ Alliance&oq=Alliance%2C+W.P.C+and+World+Health+ rganization%2C+2014+Global+atlas+of+palliative+care+at+the+end+ of+life+London%3A+Worldwide+Palliative+Care+ Alliance&aqs=chrome.69i57.1722j0j8&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8#

- [Google Scholar]

- Kerala, India: A regional community-based palliative care model. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:623-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ten Achievements in Ten Years Pallium India-Care Beyond Cure. 2014. Available from: http://www.palliumindia.org/programs/ten-achievements-in-ten-years/

- [Google Scholar]

- Indian Association of Palliative Care Academics. Available from: http://www.palliativecare.in/academics-2/

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative Care Fellowship – Indo-American Cancer Association. Available from: http://www.iacaweb.org/what-we-do/palliative-care-fellowship/

- [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Palliative Medicine. Available from: http://www.instituteofpalliativemedicine.org/

- [Google Scholar]

- India. National Fellowship in Palliative Medicine in India: Apply before 15 June. Available from: http://www.ehospice.com/india/default.aspx?tabid=10675&ArticleId=15264

- [Google Scholar]

- Home-INCTR Palliative Care Handbook. Available from: http://www.inctr-palliative-care-handbook-wikidot.com/

- [Google Scholar]

- Education in Palliative and End-of-Life Care: Feinberg School of Medicine: Northwestern University. Available from: http://www.epec.net/EPEC/Webpages/epecindia.cfm

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative Care Jiv Daya Foundation. Available from: http://www.jivdayafound.org/palliative-care/

- A Call to Action for Ensuring Humane Care at the End of Life. Pallium India-Care Beyond Cure. 2017. Available from: http://palliumindia.org/2017/04/a-call-to-action-for-ensuring-humane-care-at-the-end-of-life

- [Google Scholar]

- International. The Mathura Declaration – A Call to Action to Promote Palliative and end of Life Care in India. Available from: http://www.ehospice.com/default.aspx?tabid=10686&ArticleId=22187

- [Google Scholar]

- Presentations from 1st ICPCN Conference-ICPCN. ICPCN. Available from: http://www.icpcn.org/icpcn-conference-in-india-2

- [Google Scholar]

- The impact of misuse and diversion of opioid substitution treatment medicines: Evidence review and expert consensus. Eur Addict Res. 2016;22:99-106.

- [Google Scholar]

- Documentary: Freedom from Pain. Pallium India-Care Beyond Cure. 2011. Available from: http://www.palliumindia.org/2011/07/documentary-freedom-from-pain

- [Google Scholar]

- WHO Essential medicines; 22 May. 2015. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/essential_medicines/en/

- [Google Scholar]

- Ensuring palliative medicine availability: The development of the IAHPC list of essential medicines for palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:521-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer pain management in developing countries. Indian J Palliat Care. 2016;22:373-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Formulary availability and regulatory barriers to accessibility of opioids for cancer pain in India: A report from the global opioid policy initiative (GOPI) Ann Oncol. 2013;24(Suppl 11):xi33-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Availability and utilization of opioids for pain management: Global issues. Ochsner J. 2014;14:208-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Available from: http://www.unodc.org/ungass2016/

- Funding for palliative care programs in developing countries. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:509-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- India. Palliative Care Education in India. Available from: http://www.ehospice.com/india/default.aspx?tabid=10675&ArticleId=5588

- [Google Scholar]

- Feasibility and acceptability of implementing the integrated care plan for the dying in the Indian setting: Survey of perspectives of Indian palliative care providers. Indian J Palliat Care. 2017;23:3-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care in India: Current progress and future needs. Indian J Palliat Care. 2012;18:149-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Providing Palliative Care in economically disadvantaged countries. In: Cherny N, Fallon M, Kaasa S, Portenoy R, Currow D, eds. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine. NY: Oxford University Press; 2015. p. :10-19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Constitutional and legal protection for life support limitation in India. Indian J Palliat Care. 2015;21:258-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Addressing the barriers related with opioid therapy for management of chronic pain in India. Pain Manag. 2017;7:311-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Cancer Pain Relief: With a Guide to Opioid Availability. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1996. p. :63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care for non-cancer patients in tertiary care hospitals. Int J Med Public Health. 2016;6:151-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recommendations to support nurses and improve the delivery of oncology and palliative care in India. Indian J Palliat Care. 2017;23:188-98.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical pharmacology of methadone for pain. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2008;52:879-89.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of methadone in cancer pain treatment – A review. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63:1095-109.

- [Google Scholar]

- What Special Considerations Should Guide the Safe Use of Methadone? In: Goldstein N, Morrison RS, eds. Evidence-Based Practice in Palliative Medicine. Elselvier 2013 PA; 2013. p. :39-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- How Should Methadone Be Started and Titrated in Opioid-Naïve and Opioid-Tolerant Patients? In: Goldstein N, Morrison RS, eds. Evidence-Based Practice in Palliative Medicine. Elselvier; 2013. p. :34-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Methadone for relief of cancer pain: A review of pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, drug interactions and protocols of administration. Support Care Cancer. 2001;9:73-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Therapeutic challenges in cancer pain management: A systematic review of methadone. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2014;28:197-205.

- [Google Scholar]

- Distribution of genetic polymorphisms of genes encoding drug metabolizing enzymes drug transporters-A review with Indian perspective. Indian J Med Res. 2014;139:27-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Methadone Program – Canada.ca. 2004. Available from http://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-concerns/controlled-substances-precursor-chemicals/exemptions/methadone-program.html

- [Google Scholar]

- The burden of polypharmacy in patients near the end of life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51:178-8300.

- [Google Scholar]

- Opioids for cancer pain-An overview of cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7:CD012592.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of oral methadone on the QTc interval in advanced cancer patients: A prospective pilot study. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:33-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Methadone initiation and rotation in the outpatient setting for patients with cancer pain. Cancer. 2010;116:520-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Methadone: Outpatient titration and monitoring strategies in cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;18:369-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical experience with oral methadone administration in the treatment of pain in 196 advanced cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2836-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- The journey of opioid substitution therapy in India: Achievements and challenges. Indian J Psychiatry. 2017;59:39-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Balancing improved opioid supply and safe use of opioids for cancer pain by using “Circle of safety”. Indian J Palliat Care. 2017;23:221-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Avoiding globalisation of the prescription opioid epidemic. Lancet. 2017;390:437-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Access to controlled medicines for palliative care in India: Gains and challenges. Indian J Med Ethics. 2015;12:77-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Principles of Biomedical Ethics. USA: Oxford University Press; 2001. p. :454.